Everything You Need To Know About Exercise Order

Comparing the SFR of both approaches and which to choose depending on your goals

Before we jump into the newsletter, consider checking out my new YouTube series where I take you through each of my training sessions, share some insights, and dive into banter amongst long-time friends and fellow entrepreneurs.

If you’re interested in supporting what we do, be sure to subscribe and turn alerts on to receive updates on the latest episode!

Additionally, in the coming weeks BowTiedOx and I will be releasing our first episode of our podcast (yet to be named) here on Substack. Lots to look forward to so stay tuned!

Understanding the Dynamics of Exercise Order in Training

A lot can go into deciding the order of exercises. Because of the many choices to be made, exercise order and selection is a bit of an art. Art is all about making many choices where the final product is really up for interpretation. There is no one final painting to end all paintings. There are many paintings that all involve hundreds, if not thousands, of little choices. Fortunately for us, we have fewer choices to make than those in the Mona Lisa, but there are enough considerations that make your choices for building a program somewhat unique — let me explain. Aside from the obvious question of who we are building the program for and what equipment they have/like to use (this is our palette to paint on), we have to consider a number of key questions involving exercise order:

Which exercises to start with?

Which exercises do we end on?

Which muscle groups do we focus on most heavily?

Should that be more isolation driven?

Should that be more compound driven?

What is the raw stimulus of an isolation vs. a compound?

What is the fatigue cost of isolation vs. compounds?

Which order gets us the best overall gains?

While we can and will get into the nuances of every one of these questions, today we will be focusing on probably the two questions with the most consequence: Heavy compound → isolation, or Heavy isolation → compound.

This article dives into each method's effects on raw and total muscle stimulus, fatigue costs, and injury prevention that will leave you with a better understanding of the programming for hypertrophy.

Defining Compound and Isolation Exercises

Compound exercises are multi-joint movements that work several muscle groups simultaneously. They typically involve larger, primary muscle groups and secondary supporting muscles like the Barbell Squat, which primarily targets the quads but also engages the glutes, hamstrings, and lower back. It is a staple in leg training for its effectiveness in building strength and size.

Isolation exercises focus on a single joint and primarily target one muscle group. These exercises are excellent for honing in on specific muscles, improving muscle imbalances, or adding volume to a workout without excessive fatigue. They typically involve less overall bodily stress and are useful for targeting muscles that may be underdeveloped or recovering from injury. The Leg Extension is a quintessential isolation exercise for the quads, for example. It isolates the quadriceps, allowing for focused muscle engagement and is less taxing on the overall body.

With the Barbell Squat as our most compound exercise for quad development, and leg extensions as our least compound (most isolation) for quad development, there are exercises that fall in between. More stabilized movements like the Leg Press, Hack Squat, and Smith Machine Squat fall into this category.

Benefits and Costs of Heavy Compounds First

Compound exercises such as the Barbell Squat or Hack Squat work multiple muscle groups simultaneously and lend themselves to driving raw force. When performed fresh, at the beginning of a workout, our ability to use heavier weights, due to zero prior fatigue, results in the greatest output of total raw muscle stimulus. In other words, we get the greatest gains from putting heavy compounds at the start of the session. But this comes at a cost…

The involvement of more muscle groups and heavier loads in compound exercises leads to very high fatigue. Stress on the spine (known as axial fatigue) and central body structures (systemic fatigue), typical in exercises like squats and deadlifts, has a highly taxing impact on our cardiovascular and nervous systems. Anyone who has started a leg day with super heavy squats for high reps can attest to this effect.

Benefits and Costs of Isolation Movements First

Isolation exercises, such as Leg Extensions, target individual muscle groups and provide a lower total raw stimulus compared to compound exercises. Starting a workout with isolation exercises allows for intense focus and can offer a pretty good stimulus, but not quite as good as the raw stimulus of a compound lift. But there is an upside…

Isolation exercises cause far less overall fatigue. Having no involvement of the spine (axial fatigue) and central structures (systemic fatigue), the ratio of stimulus to fatigue is probably better than starting with a heavy compound. This doesn’t mean you’ll make greater gains, however - the Heavy Barbell Squat will for sure get you the better gains. It is to say, however, that while the muscle stimulus is lower, the fatigue is WAY lower on the Leg Extensions (isolation).

This is not the end of the story, however. Next, we go beyond the first exercise and see how progressively getting more or less compound affects the totality of the training sessions, and how we can apply this to our own training.

Progressing From Heavy Compounds to Isolation

Recall from our conversations about intensity and volume, gains have diminishing returns, with studies showing as much as 65% of total gains can come from 1-4 sets taken to failure with only 85% in the 5-8 set range.

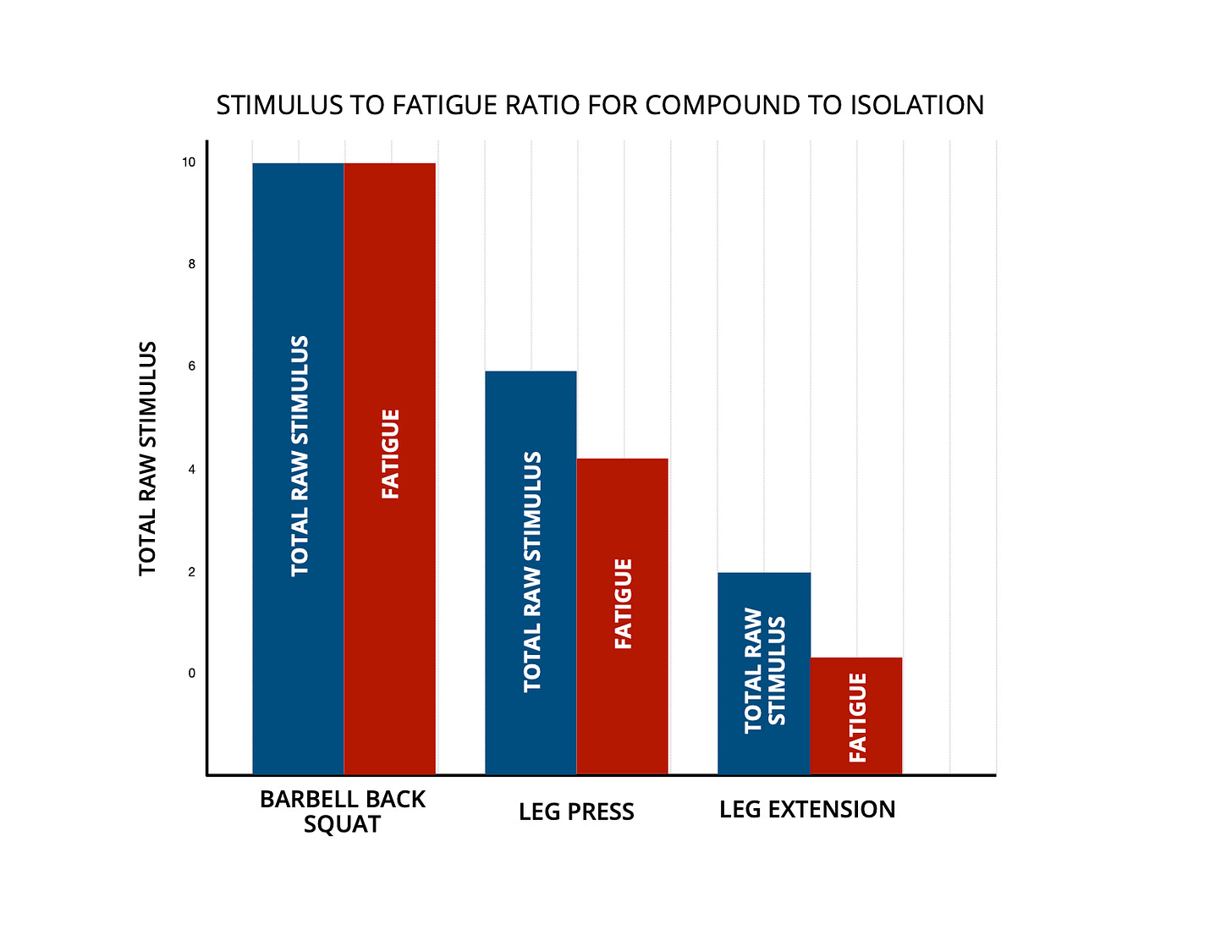

It stands to reason these first few sets would be best utilized as heavy compound movements, with what we know about total raw stimulus and heavy compounds. So with the example of a quad-dominant leg workout, we might want to start with a barbell back squat (or hack squat for the stabilization purists). Compared to a leg extension, the barbell back squat provides a higher raw total magnitude of stimulus, making it the better candidate from a straight-up gains perspective, despite the super high fatigue cost of something like a barbell back squat.

Because the fatigue was so high from loading up our bodies (and in this case, our spine) with super heavy weight on our first exercise, whatever comes after will have to be performed at a lower weight, usually for more controlled reps. Which is totally normal and fine. We’re likely still in that 1-8 set total at this point in our session, so driving as much raw stimulus as we can makes sense if our goal is to maximize gains from an efficiency standpoint.

So let’s say we move onto leg presses. The load we would use would not be as high as it would’ve been had this been the first exercise in the session, but we are still driving close to failure and working our quads super hard — great. What about on the fatigue side? Leg presses are for sure fatiguing. Not as much as barbell back squats due to no axial loading of the spine, but quite a bit higher than leg extensions.

Finally, we end up on our least compound heavy movement, leg extensions. What we know about leg extensions is that you can for sure load these up and do serious damage to your quads, but from a raw stimulus standpoint, they’ll get beaten every time by leg presses or squats. What we also know is that from a fatiguing perspective, they provide the least fatigue of the three exercises we’ve used. It makes sense that they would go last in this exercise order, considering what we’ve already put our bodies through.

From a raw stimulus perspective, heavy compounds to isolation makes the most sense, but they have their downsides.

The fatigue cost will be super high.

The risk of injury is higher.

Progressing From Isolation to Heavy Compounds

When we are fresh at the start of the workout, we train the quads in isolation using the leg extensions.

Comparing the two approaches so far, while the leg extensions may seem like child’s play compared to a heavy barbell squat, we can still load up the quads fairly decently in isolation. Will we get the same total raw magnitude of the barbell squat? No, but if we consider the comparison of ratios of total raw stimulus and fatigue, the leg extension is the superior option. Again, I am not saying that leg extensions provide more gains, just that their stimulus-to-fatigue ratio is better.

As we move further into the session, we have leg presses. Comparing the same point in both sessions, going into leg presses after barbell squats we were FAR more fatigued, resulting in better execution and raw stimulus of the leg extension with the isolation-first approach.

Finally, as we head into our most compound movement, the barbell back squat, let’s compare total raw stimulus and fatigue for both scenarios. From a total raw stimulus perspective, compound wins for sure. From a fatigue standpoint, isolation first is winning by a lot more.

The barbell back squat last in our scenario means using much lighter loads than we would at the start of a session. So from a raw stimulus perspective, it’s not quite as high, but still pretty high considering we are taking all sets close to failure, despite the magnitude of force being driven by the quads.

Which Method To Choose and Why?

Set for set, there is no question that the compound to isolation scenario will produce better results from a pure gains perspective. But as we’ve seen, the fatigue cost of the compound to isolation scenario is super high. Conversely, with isolation to compound, the stimulus isn’t as high (although high enough) but the fatigue is a lot lower.

If we are after the most gain possible, you may think that the compound to isolation scenario is better. Technically you would be right. However, the much lower fatigue cost of isolation to compound provides a uniquely better situation in which we can add more volume. In other words, we can match or improve on the gains we get from the first scenario by adding more sets, incur less fatigue, and maybe most importantly, train in a way that reduces the risk of injury.

This is a strategy used by high-level bodybuilders as they get closer to their shows where an injury could be devastating. I’m not privy to the details, but Nick Walker recently had to bow out of this year's Olympia in the last week due to a hamstring tear. As the athletes dry out, the risk of injury shoots way up and injury prevention becomes a top priority. 5x Olympia Champion CBum trained this way leading into his 5th title for this exact stated reason and you can’t argue with those results (as you can see below).

Concluding Thoughts

In conclusion, the decision between starting with heavy compounds and then progressing to isolation, or vice versa, depends largely on individual goals and circumstances. While heavy compounds first offer the greatest raw muscle stimulus, they come with higher fatigue and injury risk. On the other hand, beginning with isolation exercises provides a better stimulus-to-fatigue ratio, allowing for more volume and potentially similar gains with a lower risk of injury. Ultimately, understanding and applying these principles can lead to more effective and safer training programs, especially for those aiming for peak performance and muscle development. The key lies in balancing the benefits and drawbacks of each approach to tailor a regimen that aligns with the athlete's specific needs and goals.